Pavlov’s Rat: Scientists Demonstrate That Rats Have Imaginations

Experiments show that rats can picture something they’ve grown used to, even when it isn’t there.

Mar 29 2015

Imaginative rats are a popular trope of fiction, from Pixar's culinary dreamer Remy to the wannabe dictator Brain from Animaniacs. But do real-life rats have any ability to imagine unseen possibilities in the world around them?

According to new research from behavioral neuroscientist Aaron Blaisdell, they absolutely do. Blaisdell presides over UCLA's Comparative Cognition Laboratory, and is particularly interested in the limits of reasoning and imagination in non-human animals.

Blaisdell presented some of his latest findings in this field Sunday at the Cognitive Neuroscience Society conference in San Francisco. They are based on experiments that suggest rats are capable of intuiting the presence of a certain stimulus, even if it is not visible to them.

"The rats were trained to press a lever when lights were presented," Blaisdell told me. "But they had to pay attention to whether one or two lights were on."

One group of rats was rewarded for pressing the lever when only one light was on, but never when both lights were simultaneously shining. A second group were trained to expect the opposite scenario, and were only rewarded for pushing the lever when both lights were on, but never when only one was lit.

When the rats had been conditioned with these expectations, Blaisdell and his colleagues switched it up by covering one light and presenting the other.

"When one of the lights was covered on this test trial, the amount of times the rat pressed the lever was intermediate between the high amount they pressed on rewarded trials during training, and the low amount they pressed on non-rewarded trials during training." he said.

"This intermediate level of response suggests that rats believed the covered light might be on and thus responded with some uncertainty, but as if it might be on," Blaisdell continued.

The rats seemed to deduce the existence of something that wasn't immediately evident to them, simply because they had prior experience with it. This result suggests that rats have some form of counterfactual thinking, which is the ability to consider alternate versions of past life events, and their speculative effect on the present (for example, the statement: "if only I had invested in Google ten years ago, then I'd be rich today"). It is a sophisticated reasoning tool, and clearly extends to rats in some form.

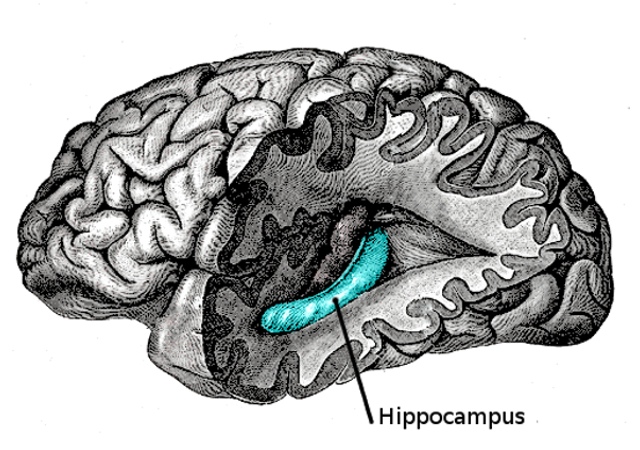

Indeed, one of Blaisdell's most compelling findings is that impairing the hippocampus portion of a rat's brain will completely change the outcome of this experiment. For context, the human hippocampus is deeply involved in counterfactual thinking.

"When we temporarily inactivated the hippocampus, the rats no longer showed the intermediate level of lever pressing when tested with one light on and the other light covered," Blaisdell told me. "They treated these test trials as if it was simple a single light trial as in training."

The new research supports the idea that rats and humans share some level of reasoning ability, and that by extension, so do many other animals. Defining the precise limits of these similarities may lead to better treatment of certain neurological disorders, like schizophrenia, autism, and Alzheimer's disease. It will also provide insights into a wide variety of biological and psychological questions.

Along those lines, Blaisdell plans to delve much deeper into the mental mechanics that underpin reasoning in rats.

(shortened for space)

Source:

https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/...ntists-demonstrate-that-rats-have-imagination

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Rats, Reasoning & Rehabilitation: Neuroscientists are Uncovering How We Reason

March 29, 2015

CNS 2015 Press Release

CNS 2015 Press Release

March 29, 2015 – San Francisco – Even rats can imagine: A new study finds that rats have the ability to link cause and effect such that they can expect, or imagine, something happening even if it isn’t. The findings are important to understanding human reasoning, especially in older adults, as aging degrades the ability to maintain information about unobserved events.

“What sets humans apart from the rest of the animal kingdom is our prodigious ability to reason. But what about human reasoning is truly a human-unique feature and what aspects are shared with our nonhuman relatives?,” asks Aaron Blaisdell of the University of California, Los Angeles. “This is the question that drives my passion for research on rational behavior in rats.”

Linking cause and effect in rats

Blaisdell’s work draws from long-understood ideas from Pavlov and others that when a rat (or dog or pigeon) observes one event followed by another, such as a tone followed by food, it forms an association between the events. After the association is formed, whenever the rat hears the tone, it expects food to follow.

But his work goes further, showing that rats reason: “What I have shown in my research is that rats not only acquire these types of Pavlovian associations between two events, but that they can form a causal link between them as well,” Blaisdell explains. The rat appears to believe that the tone causes the food.

Blaisdell and colleagues have tested the extent of these causal beliefs in a range of conditions, as presented today at the CNS meeting. For example, if a rat learns that a light is a common cause of both tone and food, then when the rat hears the tone, it makes the prediction that the light must have occurred. “And if the light had just occurred, the food, which is the other effect of the light, should also be available,” he says.

Rats, the researchers have found, also can make rational inferences about their own actions. Take the example of the light as a common cause of both tone and food. If researchers allow the rat to press a lever to turn on the tone, then the rat no longer expects food; the rat understands that it was the cause of the tone and not the light, thereby changing the expectation of food. “This is similar to predicting bad weather to arrive when you observe a drop in air pressure in the reading on a barometer,” Blaisdell explains. “You don’t predict bad weather to arrive if you tamper with the barometer and artificially make its reading drop.”

In his latest work, Blaisdell and colleagues have found that once rats observe two events together, it not only forms an association but also an expectation. For example, if two lights occur at the same time, a rat will expect one light to occur whenever the other one does. But even more remarkably, if researchers cover one of the lights so that the rat cannot see it and then the researchers present the other light, the rats take actions as though the hidden light might be on.

“They maintain an image or expectation that the light is present even though they can’t see it,” Blaisdell says. “They then use this imagined event to guide decision-making about actions that may or may not produce food, depending on the available evidence.”

This type of reasoning is the basis of counterfactual reasoning – the ability to maintain information about, and make hypotheses based off, absent events. Thus, Blaisdell says, elements of counterfactual reasoning appear to have an origin deep in evolutionary time.

Counterfactual reasoning declines in old age, especially when a neurodegenerative disease is involved. Thus, understanding this process is key to informing clinical treatments.

Blaisdell and his colleagues have found a shared neurological mechanism between rats and people for counterfactual reasoning in the hippocampus – a brain structure very vulnerable to age-related decline, including in Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers already know that the hippocampus is involved in counterfactual thinking in people. When Blaisdell’s team temporarily inactivated part of the hippocampus in rats, they were no longer able to hold in their mind the image of the absent light.

“Rats, and many other nonhuman species, continue to provide a treasure trove of information about cognition and reasoning,” Blaisdell says. “Looking at an animal is like looking into a mirror that reflects back a part of ourselves. I see as much of them in us as I see of us in them.”

(shortened for space)

Full reading at:

https://www.cogneurosociety.org/rats_reasoning_cns2015_pr/

Experiments show that rats can picture something they’ve grown used to, even when it isn’t there.

Mar 29 2015

Imaginative rats are a popular trope of fiction, from Pixar's culinary dreamer Remy to the wannabe dictator Brain from Animaniacs. But do real-life rats have any ability to imagine unseen possibilities in the world around them?

According to new research from behavioral neuroscientist Aaron Blaisdell, they absolutely do. Blaisdell presides over UCLA's Comparative Cognition Laboratory, and is particularly interested in the limits of reasoning and imagination in non-human animals.

Blaisdell presented some of his latest findings in this field Sunday at the Cognitive Neuroscience Society conference in San Francisco. They are based on experiments that suggest rats are capable of intuiting the presence of a certain stimulus, even if it is not visible to them.

"The rats were trained to press a lever when lights were presented," Blaisdell told me. "But they had to pay attention to whether one or two lights were on."

One group of rats was rewarded for pressing the lever when only one light was on, but never when both lights were simultaneously shining. A second group were trained to expect the opposite scenario, and were only rewarded for pushing the lever when both lights were on, but never when only one was lit.

When the rats had been conditioned with these expectations, Blaisdell and his colleagues switched it up by covering one light and presenting the other.

"When one of the lights was covered on this test trial, the amount of times the rat pressed the lever was intermediate between the high amount they pressed on rewarded trials during training, and the low amount they pressed on non-rewarded trials during training." he said.

"This intermediate level of response suggests that rats believed the covered light might be on and thus responded with some uncertainty, but as if it might be on," Blaisdell continued.

The rats seemed to deduce the existence of something that wasn't immediately evident to them, simply because they had prior experience with it. This result suggests that rats have some form of counterfactual thinking, which is the ability to consider alternate versions of past life events, and their speculative effect on the present (for example, the statement: "if only I had invested in Google ten years ago, then I'd be rich today"). It is a sophisticated reasoning tool, and clearly extends to rats in some form.

Indeed, one of Blaisdell's most compelling findings is that impairing the hippocampus portion of a rat's brain will completely change the outcome of this experiment. For context, the human hippocampus is deeply involved in counterfactual thinking.

"When we temporarily inactivated the hippocampus, the rats no longer showed the intermediate level of lever pressing when tested with one light on and the other light covered," Blaisdell told me. "They treated these test trials as if it was simple a single light trial as in training."

The new research supports the idea that rats and humans share some level of reasoning ability, and that by extension, so do many other animals. Defining the precise limits of these similarities may lead to better treatment of certain neurological disorders, like schizophrenia, autism, and Alzheimer's disease. It will also provide insights into a wide variety of biological and psychological questions.

Along those lines, Blaisdell plans to delve much deeper into the mental mechanics that underpin reasoning in rats.

(shortened for space)

Source:

https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/...ntists-demonstrate-that-rats-have-imagination

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Rats, Reasoning & Rehabilitation: Neuroscientists are Uncovering How We Reason

March 29, 2015

CNS 2015 Press Release

CNS 2015 Press ReleaseMarch 29, 2015 – San Francisco – Even rats can imagine: A new study finds that rats have the ability to link cause and effect such that they can expect, or imagine, something happening even if it isn’t. The findings are important to understanding human reasoning, especially in older adults, as aging degrades the ability to maintain information about unobserved events.

“What sets humans apart from the rest of the animal kingdom is our prodigious ability to reason. But what about human reasoning is truly a human-unique feature and what aspects are shared with our nonhuman relatives?,” asks Aaron Blaisdell of the University of California, Los Angeles. “This is the question that drives my passion for research on rational behavior in rats.”

Linking cause and effect in rats

Blaisdell’s work draws from long-understood ideas from Pavlov and others that when a rat (or dog or pigeon) observes one event followed by another, such as a tone followed by food, it forms an association between the events. After the association is formed, whenever the rat hears the tone, it expects food to follow.

But his work goes further, showing that rats reason: “What I have shown in my research is that rats not only acquire these types of Pavlovian associations between two events, but that they can form a causal link between them as well,” Blaisdell explains. The rat appears to believe that the tone causes the food.

Blaisdell and colleagues have tested the extent of these causal beliefs in a range of conditions, as presented today at the CNS meeting. For example, if a rat learns that a light is a common cause of both tone and food, then when the rat hears the tone, it makes the prediction that the light must have occurred. “And if the light had just occurred, the food, which is the other effect of the light, should also be available,” he says.

Rats, the researchers have found, also can make rational inferences about their own actions. Take the example of the light as a common cause of both tone and food. If researchers allow the rat to press a lever to turn on the tone, then the rat no longer expects food; the rat understands that it was the cause of the tone and not the light, thereby changing the expectation of food. “This is similar to predicting bad weather to arrive when you observe a drop in air pressure in the reading on a barometer,” Blaisdell explains. “You don’t predict bad weather to arrive if you tamper with the barometer and artificially make its reading drop.”

In his latest work, Blaisdell and colleagues have found that once rats observe two events together, it not only forms an association but also an expectation. For example, if two lights occur at the same time, a rat will expect one light to occur whenever the other one does. But even more remarkably, if researchers cover one of the lights so that the rat cannot see it and then the researchers present the other light, the rats take actions as though the hidden light might be on.

“They maintain an image or expectation that the light is present even though they can’t see it,” Blaisdell says. “They then use this imagined event to guide decision-making about actions that may or may not produce food, depending on the available evidence.”

This type of reasoning is the basis of counterfactual reasoning – the ability to maintain information about, and make hypotheses based off, absent events. Thus, Blaisdell says, elements of counterfactual reasoning appear to have an origin deep in evolutionary time.

Counterfactual reasoning declines in old age, especially when a neurodegenerative disease is involved. Thus, understanding this process is key to informing clinical treatments.

Blaisdell and his colleagues have found a shared neurological mechanism between rats and people for counterfactual reasoning in the hippocampus – a brain structure very vulnerable to age-related decline, including in Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers already know that the hippocampus is involved in counterfactual thinking in people. When Blaisdell’s team temporarily inactivated part of the hippocampus in rats, they were no longer able to hold in their mind the image of the absent light.

“Rats, and many other nonhuman species, continue to provide a treasure trove of information about cognition and reasoning,” Blaisdell says. “Looking at an animal is like looking into a mirror that reflects back a part of ourselves. I see as much of them in us as I see of us in them.”

(shortened for space)

Full reading at:

https://www.cogneurosociety.org/rats_reasoning_cns2015_pr/

Last edited: